Generative AI is the new darling of the AI species, leaving traditional AI, which everyone was enamored of for a decade, a little jealous. Jokes aside, Traditional AI, by which I mean an AI that solves classic tasks such as detection, classification, recognition, segmentation, etc. continues to be important, and still is in relatively early stages of widespread adoption in industry.

The wide chasm between AI and real-world applications continues to grow as a steady stream of advances appear regularly. Meanwhile, the work of envisioning impactful products that connect the dots between that technology and real-world use cases remains. As we know, customers do not buy technological capability. They buy products that solve their problems.

In this article I try to classify the various AIs in a systematic way so it is clearer to a user as to what AI to use, or whether even to use AI, given a problem. For ease of exposition, I will be oversimplifying things a bit, so I’d like some indulgence from the reader, at least initially. I will highlight a few nuances and exceptions along the way as I make my main points.

Structure in Data

Data has various degrees of structure. On one end you have highly structured data such as configuration parameters, sequences of operations, code, etc, which are unambiguously interpretable by both humans and machines. On the other end you have highly unstructured data, like images, speech, natural language etc. Such data are often readily interpretable by humans but not so by machines.

As humans, we thrive in an ocean of unstructured data. Images formed on our retinas are readily interpreted by our brains as we navigate through and interact with the physical world. We also produce and consume a lot of unstructured data. The bulk of human work output in today’s world is unstructured data in the form of natural language sounds, text, audio and video, be it emails, financial reports, documents, lectures, podcasts, etc. Yuval Noah Harari put it profoundly: “Language is the operating system of human civilization”. When it comes to highly structured data, however, humans are not very comfortable with it. We can interpret small amounts of it at a time, but too much of it taxes our brains. That is why reading and writing code is not as easy as speaking, reading, and writing natural language. A picture is worth a thousand words, but in some cases a paragraph may be worth a thousand lines of code. It appears that as structure in data increases, humans become less comfortable with large amounts of it, in contrast to unstructured data. Otherwise many more of us would be programming rather than binge watching TV shows.

For computers, the situation is the opposite. Algorithms require unambiguous languages for communication from humans to machines, machines to machines, and machines to humans. And those unambiguous languages are forms of structured data. Computers excel at interpreting and processing structured data, and do so at increasing speed with each new generation and breed of hardware. As for unstructured data, only relatively recently have we been able to devise practically effective algorithms to interpret them computationally.

Some nuances: Code (as in programs) is structured data, strictly speaking. Programs are unambiguously machine interpretable, yet they have some characteristics of natural language. They are designed to let us express our intents more naturally, making it easier for us to read and write code (e.g use of English words “if, while, for, exception, etc.”). And similar to natural language, a program’s context can span many lines, and influences how a given line is to be interpreted. For these reasons, in some cases, it makes sense to consider code as unstructured even though strictly speaking it is structured.

Data Transformations

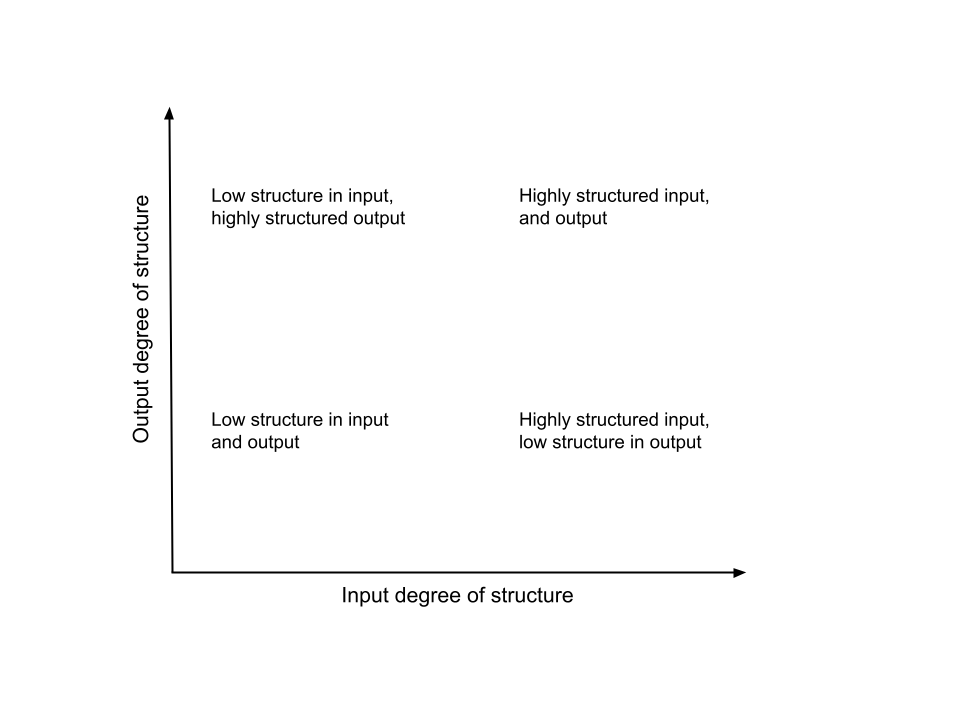

It is interesting and instructive to think about the kinds of data a given software system takes as input and produces as output. Specifically, thinking of inputs and outputs as being highly structured or not, we can classify different kinds of AI and non-AI based software broadly into four regions as shown in the figure below depending upon the degree of structure in their inputs and outputs. I will describe briefly the essential character of software in the four regions including any nuances, and then discuss their implications later.

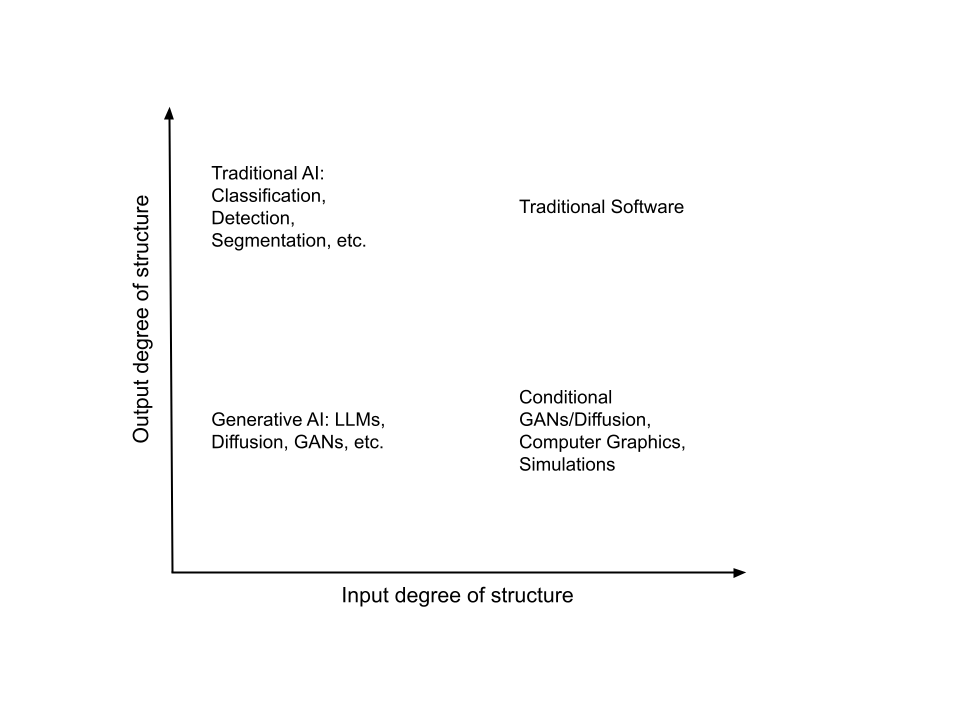

Highly Structured Input and Output

Generally speaking, traditional software takes well-defined, structured input, and produces well-defined, structured output. There is a clear right or wrong answer in every case. The very existence of software quality assurance as a discipline to ensure that software produces the correct output for every conceivable input, makes this point. While traditional software is a vast discipline, there is not much to talk about in the current context, except to note that it presents as one possible class of software system in our framework. Sometimes traditional software masquerades as “AI”, examples of which we will see below.

Low Structure in Input, High Structure in Output

Real world, non-trivial, largely unstructured data arise from stochastic processes, and so they cannot be interpreted unambiguously by traditional software. The primary goal for traditional AI has been to interpret such data, so that we can save ourselves the tedium of having to look at the data ourselves. AI models run on unstructured data, and produce small amounts of structured, actionable output - e.g. one can run a model for a “jacket” and extract color out of it so we know, for example, if there was any person wearing a yellow jacket in a camera’s feed. The AI in this case might return instances of yellow jacket detections, along with metadata. Note that even if we allow stochasticity in the output, the stochasticity itself is represented in a structured way, e.g. a “confidence” field. A small amount of structured data as output enables the AI to interface with a traditional software system, or a human, so that concrete actions can be taken in response. For example, a JSON of the data can be sent to a mobile phone if an event of interest is detected in a camera. Another example is to commit 99% of swimming pool detections in a satellite image with confidence > 0.95 to storage without human review, and to route the remaining 1% to humans for spot checking.

Low Structure in Input and Output

The latest generative AIs are powered by models trained on vast amounts of unstructured data so that when prompted, they can continue the conversation, producing natural language text, images, code, etc. as responses. Essentially, these models contain a representation of the world’s “knowledge”, as distilled from data on the open web, and fine tuned with human feedback. The unstructured character of their output makes it easy for humans to consume. We all know the innumerable ways in which generative AI tools like ChatGPT can help us come up to speed on literally any topic, very quickly. Many of us could fill a book each with mind blowing conversations we’ve had with GPT-4. Generative AI has been around for a long time, such as free text captioning of images, Many flavors of Generative Adversarial Networks (aka GANs), which enjoyed a lot of popularity in the past, and still do to some extent, are other examples. The latest generative AIs include methods like diffusion for images conditioned on natural language text prompts and images, and of course LLMs and Multimodal models.

Popular imagination for the use of generative AI has centered around creating unstructured content (e.g. essays, emails, images, art, music, etc). There is an irony here. Human created content has been growing exponentially. Digital content grew from 2 zettabytes to 64 zettabytes over the last decade. As humans, we’re often looking for specific information in this content - the proverbial needle in a growing haystack. Search engines and traditional software/AI have been tools to tame this colossal beast. A common theme among negative book reviews is that an author could have expressed her ideas in 10 pages rather than 400 pages. We often see “summary” books for sale alongside a given book, so you can get the essence without having to read all the padded fluff in the original. I believe that it is in their use as expert side-kicks alongside a human, where they can provide distilled, essential, and easily digestible information on a given topic or long form content, rather than as generators of elaborate and entertaining content, that generative AIs, particularly LLMs, are more useful, and revolutionary as an interface into AI. For example, although I do not code at work on a daily basis, I am able to accomplish programming tasks for personal projects about 10x faster today with GPT-4 for quick consults.

Some nuances: Not everything that takes in unstructured data as input and produces unstructured data as output is “Generative AI’’. For example, classic signal and image processing tasks such as histogram equalization, image enhancement, etc. are not generative AI, but a form of traditional software. Conversely, given our earlier observation that code exhibits some characteristics of natural language, code generation via LLMs, even though it is structured output technically speaking, is generative AI.

Highly Structured Input, Low Structure in Output

This is an interesting quadrant where structured data goes in and unstructured data comes out. Examples where such data transformations happen are traditional computer graphics (CG), conditional GAN/Diffusion, and simulations. Note that CG and simulations are not AI per se (see nuances).

CG takes as input, the various geometric, reflectance, irradiance, radiometric and other parameters of scene content such as the terrain, objects in the scene, light sources, etc., and the geometric and radiometric properties of a virtual camera. These parameters are all structured. CG produces as output, rendered images, which are unstructured data. Aside from entertainment, product design, architecture, art, etc. in recent times, CG has been very useful for generating training data for computer vision.

Among the various flavors of generative AI that allow control over the generation process, conditional variants of GAN and Diffusion, for example, allow the generation of unstructured data respecting a class label (which makes for structured input). These methods let us draw samples from the statistical distribution of input data that look pretty realistic. There is an interesting parallel between statistical sampling from a non-uniform distribution and these methods that deserves a separate article. To share the intuition here briefly, these methods all start with data sampled from a uniform distribution, and transform that data to make it appear as if it was drawn from the (non-uniform) distribution we want. The difference is that in the case of GAN/Diffusion, the data transformations happen via a trained deep neural network whereas in classical sampling techniques (e.g. importance or rejection sampling), the data transformations are based on hand crafted mathematics.

Simulation has been around for longer, where mathematical models seeded with data can produce synthetic data resembling real data such as network packets, log entries, the spreading of diseases, population dynamics, etc. One use for simulations is to help us develop a better understanding of the consequences of an action we might be contemplating, especially where many variables interact with each other in complex ways, making it impossible to know upfront how things will play out. Simulations also find heavy use today as generators of training data for AI.

Some nuances: In current times, the lines between CG and AI, particularly generative AI, are blurred. CG is making heavy use of AI for things such as image upscaling, style transfer, etc. In addition, the evolving field of Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs), and prior to that, Image Based Rendering (IBR), both allow the generation of novel views of a scene from a discrete set of pictures of the scene. They take a combination of unstructured and structured data as input and could be seen as belonging to both CG, as well as generative AI.

We can now fill up the graph:

A natural question from this classification is : “So what?”. For starters, it allows us to choose the type of AI we need for a given task better. Generative AI need not be the answer for all AI needs. For example, if you need small amounts of automatically actionable data from a large amount of unstructured data, a traditional AI will do. If there’s a lot of unstructured data and you are looking for a human digestible summary, then look for generative AI tools. If you want data for training a traditional AI model, be wary of using generative AI techniques, which require a lot of training data themselves to begin with, are not finely controllable, and prone to producing unrealistic data. As with any AI, garbage in will give garbage out. CG based techniques or simulations grounded on mathematical models may be more appropriate. Lastly, as you think a bit deeper and more imaginatively through this classification, interesting research and product possibilities emerge, which I will save for another time ;-).